by EnchantedWolf | May 1, 2011 | Oathtaking

I did it; I finished my soil painting as part of my First Oath. It’s not a phenomenal piece of art, let me tell you, but it was FUN. After I got started, I couldn’t stop. This is the first one I’ve ever done, and it certainly doesn’t compare with the beauty and complexity of the Tibetan Buddhists who make this art form a way of life, but, I can understand why they do it.

I discovered how to modulate the flow of the sand, I discovered where I made mistakes, like, making it way too complex and small for the plastic straw I was using to place the sand. I wound up having to ‘fill in the negative spaces’ instead of filling in the knotwork. Also, since I was using soil from my garden, I could only fill in one tone, because my soil didn’t have enough of a colour difference to really show up well. I was, in the end, content with my first effort.

I LOVED it. It was FUN, FUN, FUN. Did I mention it was fun?

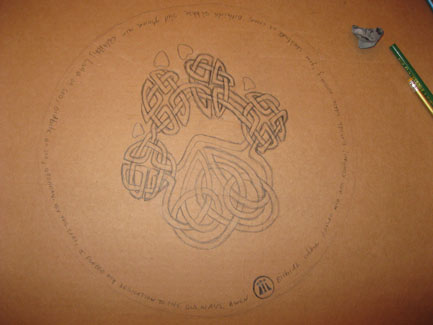

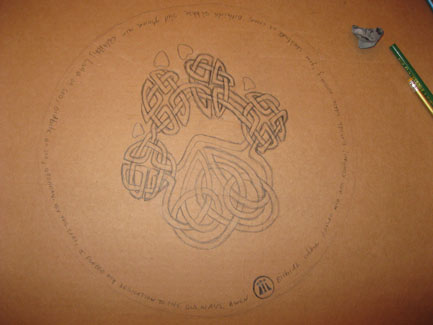

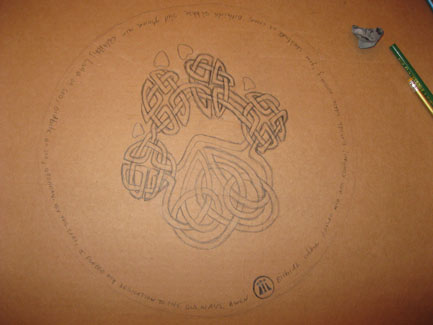

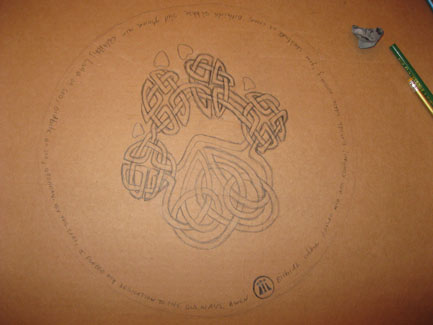

Here’s a picture of the under drawing I did. It was a pencil drawing with a 9B pencil on cardboard, slightly larger than dinner-plate size; and the Gaelic and English around the sides are part of my Oath and a Gaelic blessing of journey that is also around the sides of my drum:

My soil painting underdrawing

And here’s a picture of the finished piece:

My Finished Soil Painting

by EnchantedWolf | Apr 30, 2011 | Ellis: The Druids

Ellis speaks of Pliny at length in this chapter, and about the information we derive from him regarding the tradition of the Oak, the Oak Grove and mistletoe as a Druid Association. He points out that prior to the Alexandrian school, neither hide nor hair of a mention of an Oak Grove or mistletoe or Oak tree veneration exists, and yet, as soon as Pliny mentions it, everyone else jumps on board.

Another scholar Ellis quotes, Nora Chadwick, came up with some reasonable ideas regarding this sudden appearance, and it is simply thus: when the Romans attempted to suppress the Druids in Gaulish culture, and they could no longer teach, hold ritual, adjudicate or perform other functions openly, they retired to ‘off the beaten path’ places – like forest groves – to continue to do what they could, to teach and practice out of the Roman eye.

by EnchantedWolf | Apr 30, 2011 | Ellis: The Druids

This chapter was rather interesting to me, and I enjoyed it. (The first for the book – it just feels less dry). It speaks of the classical writers, the two schools of writing, and what conclusions and biases come from their works. I’m beginning to learn some important source facts about the Druids, and I’m starting to be able to tease apart the facts from the fancy.

The first school is that of Poseidonius, a historian and philosopher whose works were the primary source for the first set of writers, including Caesar, who actually spent a fair amount of time observing the Celts as he conquered them in Gaul, as opposed to the other writers, apparently; they seem to merely reiterate what Poseidonius has to say, with little direct experience. The thing to remember about this first set of writers, other than they seem to draw most of their information from the same source, is that their mindset was ‘Hurrah for Rome! Everyone else is a barbarian lout, or worse, and must be conquered!’.

Writers of the Poseidonius school are, aside from Poseidonius himself ;), Timagenes, Julius Caesar, Diodorus Siculus, and Strabo. It is from these writers that we have the 3 classes of Druids: Druids, Bards and Vates. We also hear of the treatment of the Heads of the enemy, the belief of immortality, and the scope of Druid social power. We also get LOTS of justification for the conquering of Gaul and the Celts by Rome. It is from Caesar that we learn the term ‘Druid’ applies to all the intelligentsia as a class of people, and not just a priesthood, although what he describes points that way. Caesar also elaborates on the Celts’ refusal to write their teachings, and also upon how the Druids in Gaul were organized. Later writers owed much to Caesar; writers such as Pliny, who first tells us of Druids’ magic, the serpent’s egg and association with the Oak Grove in his Naturalis Historia.

The second school, Alexandrian, brings writers who create encyclopaedic works, collecting and arranging known information; they cite their sources heavily, and are more favorable to the Druids themselves. It is through these writers, too, that we learn of works that are now lost.

Dio Chrysostom, in his Oratio, begins to compare the Druids to Pythagoreans and the Brahmins of India. He speaks at length in his works about the Druids as political influence and upon their intellectual achievements. He, at least, has traveled widely and has actually met the Celts of Galatia; he isn’t just passing along second-hand information, as so many others seem to be.

This constitutes the base of our knowledge from classical sources, and a sadly biased one, at that.

by EnchantedWolf | Apr 28, 2011 | High Days

This outline is by Ian Corrigan, available on the ADF site under rituals / explanations, and breaks the core down to a simple list.

- Procession

- Opening Prayers

- Grove Attunement

- Fire, Well, and Tree

- Purpose and Precedent

- Purification

- Opening the Gates

- Kindred Offerings

- Key Offerings

- Sacrifice and Omen

- The Blessings

- Work

- Closing

by EnchantedWolf | Apr 27, 2011 | Bealltainn

This fonn is for pilgrimage, making it the perfect choice for the processional from the Truck to the ritual site for Bealltainn; I love this one, even though I have trouble sustaining the higher notes and the range the chant calls for. This fonn is the signature fonn of the Céile Dé, and is considered a ‘moving’ fonn, designed for walking with sacred intent. Since the Céile Dé are Celtic Christians, I have changed this chant for my own purposes to say ‘Gods’ instead of ‘God’.

Fonn:

A dhiathan, beannaigh an chéim

O bhfuil mé ag dul

Beannaigh dom an chré

Atá fém’ chois

Translation:

Oh Gods, bless every step

that I am taking

And bless the ground

beneath my feet

source:

Fonn 2, Sacred Chants of the Céile Dé. Duncauld, Scotland: Céile Dé.